The Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collection was mainly put together by Paul Guillaume, a young passionate French art dealer. From 1914 to his death in 1934, he built up a rich collection of several hundred paintings, from impressionism to modern art, as well as African and Oceanian artworks. He became wealthy and well known, from Europe to the US, and died at the peak of his fame when he was considering opening a museum. After his death, his widow, Domenica, married architect Jean Walter and transformed and reduced the collection, while acquiring new works. When the French state bought the collection at the end of the 1950s, she wanted to name it after her successive husbands. The collection was then displayed in the Musée de l'Orangerie.

Today, its impressionist works are made up of twenty-five paintings by Renoir, fifteen by Cézanne, one by Gauguin, one by Monet and one by Sisley.

As regards the twentieth century, the museum is proud to present twelve works by Picasso, ten by Matisse, five by Modigliani, seven by Marie Laurencin, nine by Henri Rousseau, thirty-one by Derain, ten by Utrillo, twenty-two by Soutine, and one by Van Dongen.

Acquisition of the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collection

The French state’s acquisition of the Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collection in 1959 and 1963, subject to usufruct, gave the Musée de l'Orangerie its definitive appearance. Indeed, Domenica Walter (1898–1977), the widow of art dealer Paul Guillaume (1891–1934), then of architect and industrialist Jean Walter (1883–1957), fulfilled her first husband's desire to create “the first French museum of modern art” open to the public. The French state offered to exhibit the collection at the Orangerie.

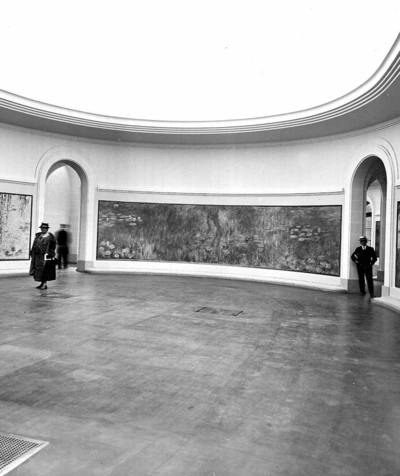

Architect Olivier Lahalle led a second renovation project from 1960 to 1965. The exhibition galleries were removed and two levels on top of each other, running the entire length, were added to the building. An imposing staircase with a banister designed by Raymond Subes (1893–1970) replaced the entrance hall to the Water Lilies. It led to a series of salons Domenica wanted to display the 146 paintings in. The collection was publicly presented in 1966, inaugurated by France’s Minister of Culture André Malraux. Domenica Walter kept the paintings until her death in 1977.

A third renovation project took place from 1978 to 1984 to strengthen the building, refurbish the rooms, and permanently house the entire collection, named the « Jean Walter and Paul Guillaume collection », as Domenica Walter had wished. The Orangerie became an independent national museum, no longer overseen by the Louvre and the Jeu de Paume, whose impressionist collections were set aside for the future Musée d’Orsay.

Paul Guillaume (1891–1934): A Visionary Art Dealer

Nothing predestined Paul Guillaume to become one of his era’s greatest art dealers. He came from a humble background and took an interest in African art, which drew the attention of poet and art critic Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918), who was also passionate about African art. The latter introduced him to the artistic avant-garde of Paris and became his mentor. In 1914, near the Elysée Palace, Paul Guillaume opened his first gallery where he exhibited works by Larionov, Gontcharova, Derain, Van Dongen, Matisse, and Picasso. Oeuvres by Modigliani and de Chirico could also be seen there. In 1918, Paul Guillaume founded a periodical called Les Arts à Paris, in which he was able to promote his artists.

In 1921, Paul Guillaume expanded his activites by setting up a gallery on Rue La Boétie, where he would display African art and painting, either alternately or at the same time. He became an advisor and art dealer to Albert Barnes, a wealthy American chemist from the US eastern seaboard. This proved decisive in leading Guillaume to fame and fortune. In 1930, he was awarded the French Legion d’honneur order of merit. He became a leading light of the Parisian smart set, alongside his wife Domenica. In their successive Paris homes, he put together one of the most outstanding collections of paintings in Europe in the 1930s. When he died suddenly at the age of forty-two, he was seriously considering offering his collection to the French state to use it to found « the first French museum of modern art ».

Domenica Walter’s Taste

Juliette Lacaze, born in 1898, met Paul Guillaume and married him in 1920. Guillaume nicknamed her Domenica. She helped him in his work as an art dealer and climbed the ladder of success with him. When Paul Guillaume died in 1934, she inherited his fortune and his extraordinary art collection, with the possibility to modify it but the obligation to put it in the Louvre Museum one day.

Domenica showed less daring taste than Guillaume and she changed the collection considerably. She parted with over two hundred works in the collection, including portraits by Modigliani, all the paintings by de Chirico, splendid oeuvres by Matisse, and all the Cubist works by Picasso. She also parted with all the collection’s African works of art.

In 1938, she married architect Jean Walter (1883–1957), a former aide-de-camp to French statesman Georges Clemenceau. Walter had made a fortune developing a mining business in North Africa. It is difficult to determine whether Walter had a personal influence on the collection. Domenica Walter settled into an apartment neighboring the Élysée Palace. There, she hung up paintings by Renoir and Cézanne, for which she had a preference and which included works she had bought herself, as well as oeuvres by Gauguin, Monet, and Sisley.

Paul Guillaume’s collection, which was characterized by visionary choices and remarkable modernity, switched to more classical choices in regard to Matisse and Picasso and to a more traditional line with impressionism: clarity of subjects and stability of compositions, with a freshness in the palette.

The French State’s Purchase of the Collection

Domenica Walter never forgot the major plan Paul Guillaume nurtured and in which she was doubtless involved: the plan to share their fabulous collection by turning it into the basis for a public museum. By making it possible for all ordinary people to admire the collection, they gave France the works of modern art the country was lacking at the end of the 1920s.

Thirty years later, at the end of the 1950s, negotiations for purchasing the collection got underway, even though Domenica Walter had modified the collection considerably and the French state had made many purchases in the field. The Société des Amis du Louvre organized a public funding pledge so the Réunion des Musées nationaux could buy the « most important works » of the collection. This initiative helped raise one hundred and thirty-five million francs of the time. Perhaps Domenica Walter did not wish to sell every item to begin with as the acquisition took place in two stages: forty-seven paintings in 1959 and ninety-nine paintings in 1963.

Domenica Walter asked for the collection to be named after her two husbands. The French state offered to place the collection in the heart of Paris, in the Musée de l'Orangerie, which the Louvre Museum still oversaw. But there was concern about the cost of the works: Domenica Walter wanted to reproduce, inside the museum, the interior of her sumptuous apartment. On January 31, 1966, she triumphantly inaugurated an initial temporary display of the collection alongside France’s Minister of Culture André Malraux. The collection became French state property when she died in 1977 and was only displayed permanently from 1984.

Les Arts à Paris

« Paul Guillaume, one of the first people the modern revolution affected. » André Breton, 1923

« Before the craze for African art began, Paul Guillaume had built up a collection of fetishes, while taking an interest in artists who were still little known […] like Modigliani and Soutine. I am not referring to his private collection, in which you could admire the most revealing works by Matisse, Derain, Henri Rousseau, and Picasso. He died prematurely—his life was like a shooting star.» That was how art dealer Ambroise Vollard referred to Paul Guillaume (1891–1934), a young art dealer who was trained and advised by Guillaume Apollinaire (1880–1918).

The poet, who, in 1911, came across this young aficionado of what was then called « primitive arts », introduced him to the artistic avant-garde and guided him in his choices when he opened his first gallery in 1914. Paul Guillaume applied the poet’s taste with brio, buoyed by a context that was paradoxically dynamic for the arts during World War One. The two luminaries of French modern art, Matisse and Picasso, whose works he displayed in a comparative display in 1918 that remained famous, formed the heart of a modern Paris school.

Two trends emerged from this school. On the one hand, there were isolated figures like Utrillo, Modigliani, and Soutine, who developed the notion of « modern primitivism », epitomized by Henri Rousseau’s works and African and Oceanian art. On the other hand, there were works by André Derain and Marie Laurencin, or Picasso and Matisse in the 1920s, which brought a revival in figurative art. They drew inspiration from the late works of impressionist masters Cézanne, Monet, and Renoir that had been rediscovered.

The Musée de l’Orangerie collection therefore reflects a particular moment in the history of modern art in Paris—the era of the periodical Les Arts à Paris, which Paul Guillaume founded in 1918, and the « modernist performances » that took place in his gallery and which included recitals from composers Éric Satie, Georges Auric, and Claude Debussy, readings from Blaise Cendrars and Guillaume Apollinaire, and presentations of metaphysical paintings from Giorgio de Chirico. Until his death in 1934, Paul Guillaume never stopped alluding to the tutelary shadow of the poet, who died early, in regard to the collection and first modern art museum he envisaged: « His clear-sighted passion and crusading spirit, given expression in lyrical beauty and able to combine a profound science with graceful charm, made him one of the most brilliant promoters of the works that were emerging. »