Monet’s Great Project

The Nymphéas [Water Lilies] cycle occupied Claude Monet for three decades, from the late 1890s until his death in 1926, at the age of 86. This series was inspired by the water garden that he created at his Giverny estate in Normandy. It resulted in the final great panels donated by Monet to the French State in 1922, and which have been on display at the Musée de l’Orangerie since 1927. The word nymphéa comes from the Greek word numphé, meaning nymph, which takes its name from the Classical myth that attributes the birth of the flower to a nymph who was dying of love for Hercules. In fact, it is also a scientific term for a water lily. The famous water lily pond inspired Monet to create a colossal work composed of almost 300 paintings, over 40 of which were large format. Three tapestries were also woven from the Nymphéas paintings, thus affirming the decorative nature of these series.

L'étang des Nymphéas à Giverny, en 1921

Musée d'Orsay

Acquisition, 2006

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

See the notice of the artwork

Two types of composition were defined by the artist at the beginning of the cycle. The first includes the edge of the pond and its dense vegetation: this is seen in the Bassins aux nymphéas of 1899-1900 [Water Lily Pond], then in the Pont japonais [Japanese Bridge] from the later years. The second, in contrast, plays on the emptiness, and includes only the surface of the water with flowers and reflections interspersed. This is seen in the Paysages d’eau [Water Landscapes] (1903-1908), close-ups in a tightly framed composition, organized in series, in which each element is presented as a fragment. This composition is also, and above all, a wall decoration. Although the idea for the project to create a circular series of decorative paintings had been taking shape since 1897, it was in 1914 that the painter decided henceforth to put all his energies into producing his « great decoration. » This took its final form in the arrangement in the Orangerie: a panoramic frieze laid out almost seamlessly, and enveloping the viewer in two elliptical rooms.

Claude Monet devant sa maison à Giverny, en 1921

Musée d'Orsay

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Alexis Brandt

See the notice of the artwork

Monet and Clemenceau. The Gift to the State

It was in 1914, at the age of 74, when he had just lost his son and could see no hope for the future, that Monet felt a renewed desire to « undertake something on a grand scale » based on « old attempts.» In 1909, he had already told Gustave Geffroy that he wanted to see the theme of the water lilies « carried along the walls. » In June 1914, he wrote that he was « embarking on a great project.» This undertaking absorbed him for several years during which he was beset by obstacles and doubts, and when the friendship and support of one man proved decisive. This was the politician Georges Clemenceau. They met in 1860, lost touch, and met up again after 1908 when Clemenceau bought a property in Bernouville near Giverny. Monet shared Clemenceau Republican’s ideas, and we also know of Clemenceau’s keen interest in the arts. During the war, Monet continued his work alternately in the open air, when the weather was suitable, and in the huge studio that he had had built in 1916 with roof windows for natural light. On November 12, 1918, the day after the Armistice, Monet wrote to Georges Clemenceau: « I am on the verge of finishing two decorative panels which I want to sign on Victory Day, and am writing to ask you if they could be offered to the State with you acting as intermediary. » The painter, therefore, intended to give the nation a real monument to peace. At that time, when it was still not certain where the decorative series was destined to live, it seems that Clemenceau managed to persuade Monet to increase this gift from just two panels to the whole decorative series. In 1920, the gift became official and resulted, in September, in an agreement between Monet and Paul Léon, director of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, for the gift to the State of twelve decorative panels that Léon would undertake to install according to the painter’s instructions in a specific building. However, Monet, prey to doubt, continually reworked his panels and even destroyed some. The contract was signed on April 12, 1922 for the gift of 19 panels, but Monet, still dissatisfied, wanted more time to perfect his work. Clemenceau wrote to him in vain that year « you are well aware that you have reached the limit of what can be achieved with power of the brush and of the mind. » But, in the end, Monet would keep the paintings until his death in 1926. His friend Clemenceau then put everything into action to inaugurate the rooms for the Water Lilies in strict accordance with Monet’s wishes.

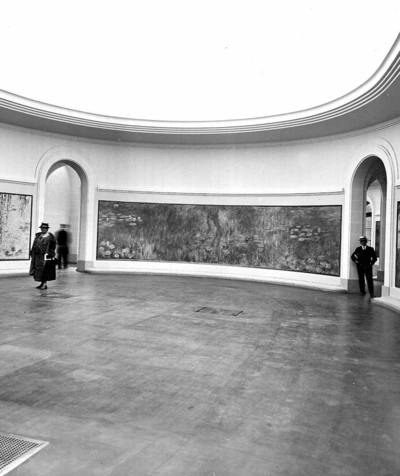

Eight panels, a unique exhibition

The Musée de l’Orangerie houses 8 of the great Nymphéas [Water Lilies] compositions by Monet created from various panels assembled side by side. These compositions are all the same height (6.5 ft/1.97m) but differ in length so that they could be hung across the curved walls of two egg-shaped rooms. The artist left nothing to chance with this set of paintings that he had long pondered over and that were displayed according to his wishes in conjunction with the architect Camille Lefèvre and with the help of Clemenceau. He planned out the forms, volumes, positioning, rhythm and the spaces between the various panels, the unguided experience of the visitor through several entrances to the room, the daylight coming in from above that floods the space when the sun is out or which is more discreet when the sun is masked by clouds, thus making the paintings resonate according to the weather.

© Albert Harlingue / Albert Harlingue / Roger-Viollet

The whole set is one of the most vast and monumental creations in painting made in the first half of the 20th century and covers a surface area of 200m2 (2,153 sq ft ). The dimensions and area covered by the painting envelop the viewer in over nearly 100 linear meters (328 linear feet), where a landscape of water punctuated with water lilies, willow branches, reflections of trees and clouds unfolds, creating « the illusion of an endless whole, of a wave with no horizon and no shore », as Monet put it. The paintings and their layout echo in the orientation of the building, as the placement of scenes with sunrise hues are to the east and those with hues of the sunset are to the west. Thus, the representation of a continuum in time and space is materialized. In an equally suggestive way, the elliptical shape of the rooms draws out the mathematical symbol for infinity. The Water Lilies paintings at the Musée de l’Orangerie have sometimes had to contend with various events and happenings. In particular, the roof of the second room was damaged during the 1944 bombings as well as one of the compositions, while the other panels remained miraculously unharmed. The 2006 renovation was also the chance to restore the Water Lilies room to its original state, a state that had been lost during the renovation work done in the 1960s that obstructed the natural light Monet had wanted.

The posterity of the Water Lilies

A gift from Claude Monet to France given the day after the armistice of November 11, 1918, the Water Lilies paintings were displayed according to his design in the Orangerie in 1927, a few months after his death. However, the set of paintings was not met with public enthusiasm at that time. In fact, in 1927 Impressionism seemed to be discredited by the artistic revival advocated by the avant-garde movements that had burst onto the scene in the early 20th century: Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism, Dada, Surrealism, etc. The public stayed away from the Water Lilies rooms for several decades still to come. The museum itself sometimes even built temporary walls up around them to hang paintings for temporary exhibitions, thus hiding Monet’s work. It wasn’t until after the Second World War and particularly with the arrival of a new modern art hall in New York that a new glance was cast upon the work of the late Monet. In the 1950s, signs of renewed interest multiplied. In 1952, André Masson published an article comparing the rooms of the Orangerie to « the Sixtine Chapel of Impressionism », private collectors began purchasing paintings from the Water Lilies collection that remained in the painter’s studio, and most of all the MOMA in New York purchased and displayed one of the great paintings in 1955. Subsequently, numerous formal similarities came to light between the abstract art of the New York School that had characterized artistic production from the late 1940s in the United States (Pollock, Rothko, Newman, Still, etc.), and the lyrical abstraction in Europe and the old master’s creations. In fact, the appearance of Monet’s Water Lilies was like the birth of decentralized painting in the West where no one part of the painting dominates another, creating an All-Over painting style. American art critic Clement Greenberg revealed this line of descent and showed how Monet’s testament work was the catalyst for a new style of painting.

The fascination the Water Lilies cast over the public and artists remained unchanged with later generations, including Joan Mitchell, Riopelle, and Sam Francis. But beyond the All-Over style, Monet also invented something that today seems common but was ahead of the times in his era: the idea of environment, which has fed all currents of art all the way through to the present, from Minimalism to the most contemporary generations. Numerous artistic achievements creating a space dedicated to artistic contemplation can also be seen as a legacy of the Water Lilies of the Orangerie. In particular the Rothko Chapel in Houston, Barnett Newman’s Stations de la Croix [Stations of the Cross] in the National Gallery in Washington as well as Twombly’s La Bataille de Lépante [The Battle of Lepanto] at the Brandhorst Museum in Munich come to mind.