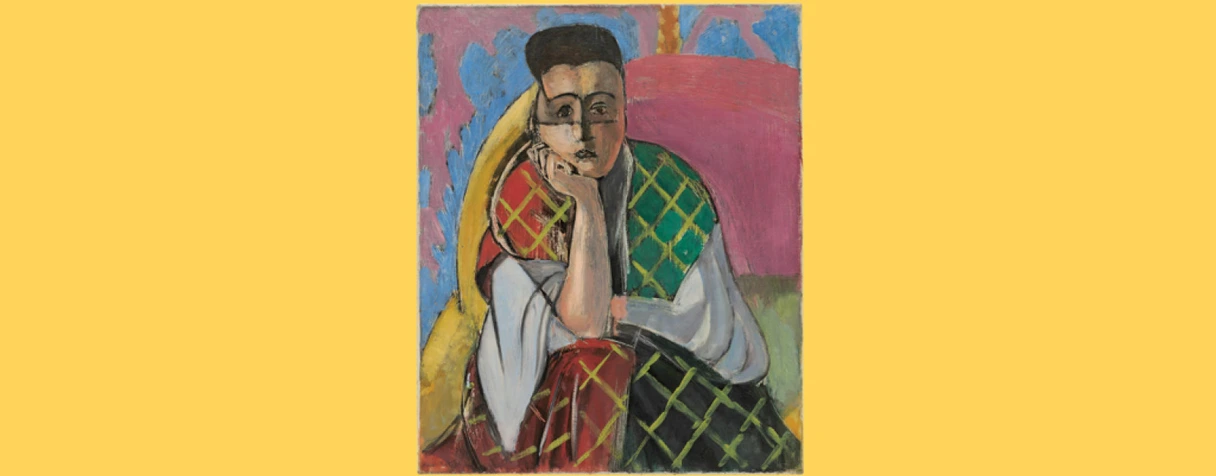

Matisse. Cahiers d'art, la svolta degli anni '30

Femme à la voilette, 1927

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

© Succession H. Matisse / © Digital image, The Museum of Modern Art, New York / Scala, Florence

The 1930s marked a turning point in the œuvre of Henri Matisse (1869-1954). He was achieving success with his paintings of interiors and reclining nude female figures produced in Nice, yet he was feeling weary and insecure. With age and fame came uncertainty, a need to revive the innovative style he showed during his time in Paris. After a long trip, he changed scale and produced The Dance, a vast wall composition intended for the Barnes Foundation in Merion in the United States, which set him on a new path on the eve of his sixtieth year. While being celebrated by a number of retrospectives in Berlin, Paris, Basel and New York, Matisse reassessed his practice resulting in him further exploring drawing and illustration and taking a serial approach to sculpture.

Mural decoration, a subject of much artistic and social debate in the 1930s, profoundly transformed Matisse’s approach to painting, reigniting his inquiry into the relationship between line and colour, resolved gradually by the brightly coloured gouache on paper he experimented with for The Dance. Matisse’s artistic activity was at the time closely followed by Cahiers d’art, an avant-garde art journal launched in 1926 by Christian Zervos. In a period of intense research, Matisse’s oeuvre became radical and at the centre of debates on ideas addressed by the journal, which embodied international modernism.

World tour

In 1930, Matisse embarked on the greatest voyage of his lifetime, to Oceania, in the footsteps of Gauguin. He travelled for over six months, crossing the Atlantic and then the United States east to west, from New York to San Francisco via Chicago and Los Angeles. He then spent three months in Tahiti, returning through Martinique and Guadeloupe. The trip had a lasting effect on Matisse, from the vast horizons, blue skies and skyscrapers of New York to the light refracted on the clear water of the Southern seas. Painting next to nothing and drawing hardly at all, he did however take about fifty photos and described his impressions in his letters. These themes and motifs represent a drastic departure from the exoticism of his indoor reclining nudes. They would re-emerge in his later work. No sooner had he returned to France than he took off again for the US to sit on the jury of the Carnegie Prize, in Pittsburgh, then to produce a mural decoration for the Barnes Foundation in Merion, near Philadelphia: The Dance, a tangible sign of revival.

The Dance

On 27 September 1930, art collector Albert C. Barnes commissioned Matisse to produce a large mural for the main hall at his foundation in Merion, near Philadelphia. Matisse was excited by the idea of working at such a monument scale, reformulating the foundations of his art and radically changing his formal processes. It ties in with the theme of the dance that first appeared in 1906 in The Joy of Life, already part of the Barnes collection. During this long and complex genesis, Matisse abandoned his first composition, even though it had been drawn and painted on large canvases, becoming The Uncompleted Dance.

After a short stay in Padua, Italy, where he went to see the frescoes by Giotto (1267-1337), which he found ‘absolutely extraordinary in their clarity of composition’, he started again with new panels, practising a brand new method whereby his composition was developed using shapes cut out from gouache-painted paper. The entire piece was then painted in large flat tints of blues, pinks, blacks and greys. Due to incorrect measurements, Matisse produced two versions. In May 1933, The Dance was installed at Merion, while the first, titled La Danse de Paris, was completed later

Drawing

At the turn of the 1930s, while his painted production had dwindled, Matisse threw himself into drawing and engraving, as if it were a reflexive and plastic form of exercise. His illustrations commissioned by the publisher Skira for Poésies (Poems) by Stéphane Mallarmé was conducted in counterpoint to the project of The Dance. It further developed his conception of the relationship between text and image, parallel and autonomous. He reapplied this principle in 1934, in another publication: Ulysses by James Joyce. His illustrations were more inspired by scenes from The Odyssey, resembling a soft melodic line, underlying the words. These engravings echo those by Picasso for Metamorphoses by Ovid (1930) as well as Vollard Suite (1933) in which re-emerged the theme of the struggles of love between nymphs and fauns. Matisse introduced a jagged and complex style with his piece Nymph in the Forest, known as Verdure (1935-1943). Large charcoal drawings produced from 1935, featuring Lydia Delectorskaya as a model, expressed a liberated and reclaimed form of sensuality heralding a revival of his painting.

Method

Matisse’s experience of producing on site The Dance profoundly changed his method, which became more conceptual. Matisse observed this in 1934: ‘These periods devoted to works of the imagination that were completely new to me… have developed an aspect of my mind.’ In addition to employing paper cutouts, pinned to the canvas so as to lay out his monumental composition, the painter captured in a series of photos the progress of his work. These in-progress photographs meant to stay in the privacy of his studio were nonetheless soon published, notably in Cahiers d’art which in 1935 presented the genesis of The Dance.

These conceptual tools, which echo his serial sculptural work — the heads of Henriette (1929), — were used for his paintings from 1935 in keeping with a more synthetic and stylised resolution marked by the idea of decoration. As such, there are over 20 in-progress photographs for Large Reclining Nude (1935) and 10 for Woman in Blue (1937). In 1938, Matisse produced for the apartment of Nelson Rockefeller The Song, a large colourful and stylised decorative piece, the in-progress photographs of which were published in Cahiers d’art the following year. Several years later, in 1945, the artist showed at the Maeght Gallery his paintings surrounded by large prints from earlier in-progress photographs in a highly contemporary and deliberately formalist approach.

The winter garden

By the end of the 1930s, Matisse was in a period of revival; his pictorial work produced in his new bright and spacious studios in Nice was particularly inventive. On the fourth floor of Place Charles-Felix then from 1938 at the Regina, once a prestigious hotel, he set up studio inside ‘winter gardens’. A series of paintings of nudes or figures wearing Roman blouses and jewellery were set against backdrops featuring enormous philodendrons and aviaries housing exotic birds. Matisse’s vitality had returned in his work as evidenced by a vibrant, at times hesitant, tension between line and colour, a clear arrangement of flat tints and the profusion of ornamental motifs.

His momentum was cut short by France’s entry into war and subsequent occupation. Planning to leave France in early May 1940, Matisse chose to stay, seeing a departure as a form of desertion. His health began to deteriorate. He had an operation in 1941 while his daughter Marguerite joined the Resistance. The ‘second chapter’ that followed became a new link in the chain of Matisse’s art